Executive Summary

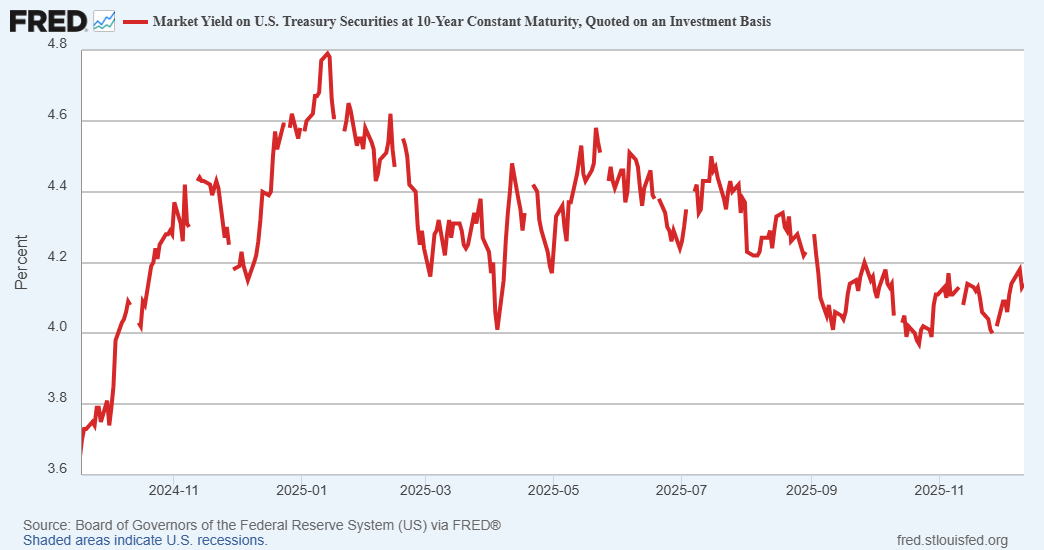

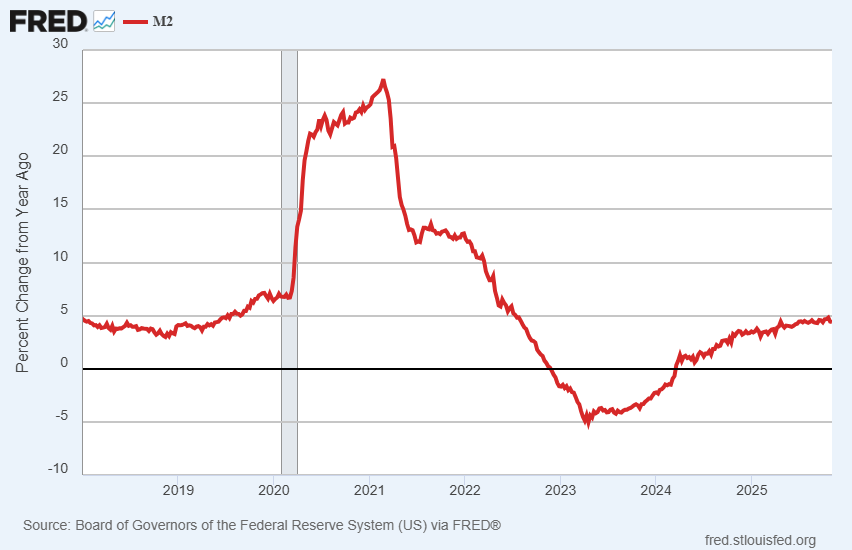

The Federal Reserve began cutting short-term interest rates again in September 2024 to address a weakening economy; however, the bond market remains skeptical about the effectiveness of these measures in controlling inflation. Despite several rate cuts and the introduction of Reserve Management Purchases (RMPs) – a form of Quantitative Easing – the yield on the 10-year Treasury Note has increased (2nd graph), reflecting persistent inflation concerns. The Fed’s actions have not significantly lowered borrowing costs for consumers, largely because high debt levels and stagnant incomes limit their ability to take on more debt. And lower short-term rates punish savers, while rewarding debt. Meanwhile, government stimulus efforts risk further increasing inflation by boosting the money supply (M2, 3rd graph). Historically, the Fed’s tools have struggled to influence long-term rates, which are driven by economic growth and inflation expectations – although a recessionary economy would do the trick. The solutions require fiscal responsibility and debt reduction, rather than repeated reliance on easy money policies, which may worsen inflation and threaten economic stability in a debt-ridden economy. Doing the same thing over and over expecting different results – insanity!

For further analysis, continue to read The Details below for more information.

“There is always an easy solution to every problem – neat, plausible, and wrong.”

–H.L. Mencken

The Details

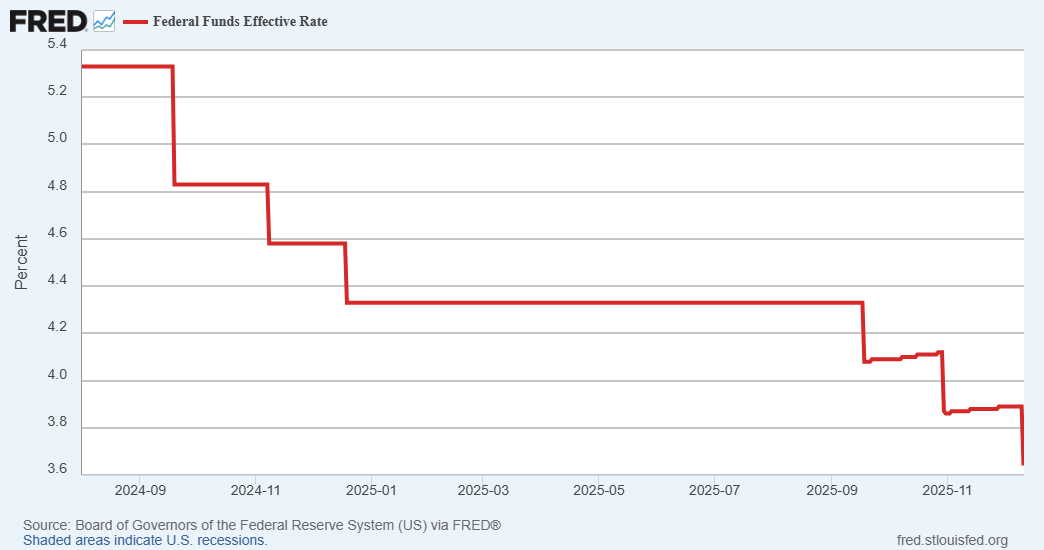

In September 2024, the Fed started cutting short-term interest rates with a 0.50% reduction in the Federal Funds Rate (FFR) This brought the target range to 4.75% – 5.00%. Recognizing the weakening economy, the Fed followed through with two more 0.25% rate cuts in 2024. As signs of potential inflation remained, the Fed held off further cuts until September 2025. In September, October and December the Fed cut the FFR three more times at 0.25% each time. With employment rapidly deteriorating and the housing market slowing, the Fed hoped the rate cuts would lower mortgage and other loan rates spurring a resurgence in housing and consumer spending. Certain important data releases have been delayed, with blame placed on the government shutdown. It is likely that the Fed has seen portions of the unreleased data, which likely confirm the slowdown. With this in mind, not only has the Fed dropped the FFR, but in December they announced a return to Quantitative Easing (QE). Only they are not calling it QE. The Fed reported they will begin buying $40 billion in Treasury Bills each month in a program they are calling Reserve Management Purchases (RMPs). (If it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck…well you know!) The Fed distinguishes this from prior QE programs by pointing to the fact that they are not focusing on longer term interest rates, [yet]. Notice the series of FFR cuts in the graph below.

The bond market is not convinced that the inflation battle has been conquered. When the Fed began dropping the FFR on September 18, 2024, the yield on the 10-year Treasury Note was 3.70% as shown in the graph below. After 1.75% in FFR rate cuts, the 10-year yield remains about 0.50% higher than when they started cutting the FFR. The reduction in the FFR has merely steepened the yield curve as the gap between short-term and long-term rates grows.

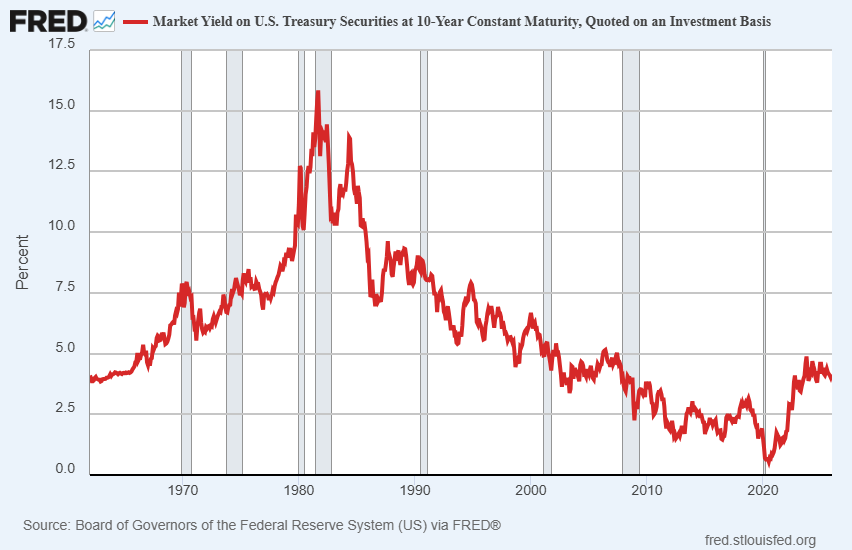

The goal of reducing loan rates so consumers can borrow and spend more is not playing out as expected. The problem is most consumers are already too far in debt, and their incomes are not growing fast enough to add more indebtedness. The cut in short-term rates actually hurts savers as rates on safe investments such as savings accounts, CDs and short-term Treasuries fall. As more companies lay off employees, people tend to focus their spending on necessities. The Fed does not control long-term interest rates, although they tried with their prior QE programs. Today, if you talk about the prior QE programs, you will hear that they helped lower interest rates. But, an interesting fact, that escapes most pundits, is that although long-term rates did fall slightly over the years from November 2008 through October 2014, if you examine the yield on the 10-year Treasury for the specific time frames of each QE program, yields actually rose during QE 1, QE2, QE 3, and QE4 (Covid). Only during Operation Twist did the 10-year yield actually fall, and only by about 0.25%. The real drop in long-term yields came with the shutdown of the economy during Covid. The point is that the Fed does not actually control long-term yields. Long-term yields are determined based upon economic growth and inflation expectations.

The Fed believes by lowering the FFR and initiating their RMP (i.e. QE) they can lower borrowing rates for consumers. The bond market is weighing the risk of recession versus the risk of inflation. The timing of the recession will play heavily on whether long-term rates drop. The Federal Government is attempting to stave off a recession by implementing stimulus measures. The tariff “dividend” of $2,000 per family will add to inflationary pressures. Typically, as unemployment rises, consumption falls and a recession arises. This initiates a “flight to safety” as investors dump stocks and purchase Treasury Securities. The rapid increase in demand forces prices up and yields down. Then when stimulus funds are issued, funded by deficits/Treasury issuance, which is paid for by the Fed (QE), the money supply (M2) jumps, and inflation expectations rise. My theory of why there was little inflation during the QE programs prior to Covid is due to the mechanism for implementing QE. (A topic for another day.) However, inflation did appear, just as asset inflation instead of goods/services price inflation. The simplified reason is investors who normally would buy Treasuries were crowded out, thanks to the Fed, and decided to reach for yield in the asset (stocks, real estate, etc.) markets. However, when Covid hit and the Federal Government went crazy with the amount of stimulus and PPP (forgivable) loans, M2 soared followed by a surge in inflation.

So, now the Fed is walking a tightrope. They want to prevent a recession by lowering the FFR and implementing RMP. However, the Federal Government’s stimulus plans will increase M2 and push prices higher. Inflation expectations will push long-term rates higher. Higher interest rates are dangerous in a debt-laden economy, especially with $38 trillion in Treasury debt.

A current 10-year Treasury yield of around 4.18% seems high to many, as the Fed and politicians scream for lower rates. However, over the long-term, except during the unprecedented times since the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, the average yield on the 10-year Treasury was higher, not lower. (See the graph below) There are some economists, including Peter Schiff, who claim the Fed should be raising the FFR, not lowering it. By lowering it he expects upward pressure on inflation.

The Fed is notorious for being late and/or wrong on the economy. Their current stance is to try and boost spending by lowering rates. However, their tools have not been very successful at lowering long-term interest rates in the past. Although, a recessionary economy will do the trick. Reading the tea leaves, they see the weakness in the economy and want to loosen monetary policy. The problem is their actions over the prior 17 years have exacerbated the problem, continuously kicking the can down the road. Today, the end of the road is becoming visible, and the old solutions present a dilemma.

The focus should be on debt reduction and fiscal responsibility. Punishing savers with low interest rates and rewarding debtors is not the answer. Flooding the economy with easy money will increase M2 and push inflation higher. Higher inflation triggers higher interest rates which kills a debt-laden economy. There is no easy solution, but we all know what it means to “try the same thing over and over expecting different results.”

The S&P 500 Index closed at 6,827, down 0.6% for the week. The yield on the 10-year Treasury

Note rose to 4.20%. Oil prices decreased to $57 per barrel, and the national average price of gasoline according to AAA fell to $2.91 per gallon.

© 2024. This material was prepared by Bob Cremerius, CPA/PFS, of Prudent Financial, and does not necessarily represent the views of other presenting parties, nor their affiliates. This information should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. An index is unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index. Actual results, performance or achievements may differ materially from those expressed or implied. All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however we make no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

Securities offered through Registered Representatives of Cambridge Investment Research, Inc., a broker/dealer, member FINRA/SIPC. Advisory services offered through Cambridge Investment Research Advisors, Inc., a Registered Investment Advisor. Prudent Financial and Cambridge are not affiliated.

The information in this email is confidential and is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended addressee and have received this message in error, please reply to the sender to inform them of this fact.

We cannot accept trade orders through email. Important letters, email or fax messages should be confirmed by calling (901) 820-4406. This email service may not be monitored every day, or after normal business hours.