Executive Summary

A recent article in the Financial Times suggests that the Fed pushing interest rates higher has led to a windfall profit for large banks of almost $1 trillion at the expense of depositors. In this missive I will review changes in Fed policies, including growing bank reserves exponentially, and paying interest on those reserves. I will show how the Fed’s new policies have led to tremendous losses for the Federal Reserve Bank. I also illustrate in The Details below how the prime lending rate correlates with changes in the Fed Funds Rate and how this differs from the rate of change in the interest rate paid to depositors. This newsletter is slightly longer and, in some respects, more technical than others; however, I encourage you to at least skim the technical parts and read through to the end.

Please proceed to read The Details below for more information.

“Let me issue and control a nation’s money and I care not who writes the laws.”

–Mayer Amschel Rothschild

The Details

A recent article in the Financial Times entitled, “Fed’s high-rates era handed $1trn windfall to US banks” suggests that higher interest rates have helped large banks get fat at the expense of depositors. Historically, banks earned interest by loaning funds to borrowers, purchasing Treasury securities or loaning funds to other banks in the Federal Funds market.

Everything began to change in 2008. In October 2008, according to an Economic Brief from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond , “the Federal Reserve began paying banks interest on the reserves they hold. This action was intended to remove the implicit, distortionary tax that reserve requirements impose on banks, as well as help the Fed maintain the fed funds rate at its target. Going forward, interest on reserves is likely to simplify monetary policy implementation, as well as allow the Fed to pursue separate monetary and credit policies. The thought process was that “Paying interest on required reserves avoids the implicit tax that reserve requirements impose on banks, which is equal to the income banks could have earned by using those funds for profit-generating loans and investments.”

The Fed would use the interest rate paid on excess reserves as a means of establishing a floor on the Federal Funds (inter-bank lending) Rate. The use of IOR (interest on reserves) as a means of controlling the Fed Funds Rate as well as for adjusting monetary and credit policies, originated out of the Financial Crisis in 2008-2009. The extreme Quantitative Easing policies, which arose out of the Financial Crisis and were pushed to their limits during the pandemic, resulted in large banks swimming in reserves. In an attempt to spur lending, the Fed eliminated the reserve requirement on banks in March 2020. However, the Fed continued to pay interest on reserves. One would think this would have eliminated the “distortionary tax” for which they justified the implementation of IOR. The details of these topics are too expansive to illuminate in a brief newsletter.

Suffice it to say, banks now have a fourth option for earning interest, interest earned on reserves and paid for by the Fed. Back to the Financial Times article, their claim is that interest earned by banks either through IOR or from loaning funds to other banks has risen much more than the amount passed through to depositors. With interest rates on Reserves and Fed Funds rising above 5%, according to the FT article, “At the end of the second quarter, the average US bank was paying depositors interest at the annual rate of just 2.2 per cent, according to regulatory data that includes accounts that do not pay interest at all…At JP Morgan and Bank of America, annual deposit costs were 1.5 per cent and 1.7 per cent, respectively, according to this data.

Those lower payments to depositors generated $1.1 tn in excess interest revenue for the banks, or about half of the total dollars banks brought in during that time, according to the FT’s calculations […]

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank and others in early 2023 forced many mid-sized and smaller banks to raise their rates in order to keep depositors from fleeing. Larger banks saw an influx of cash during the flight for safety, allowing them to delay the need to match the higher rates elsewhere.” […]

“The last time the Fed raised interest rates, from early 2016 to until early 2019, US banks captured 77 per cent of the benefit.”

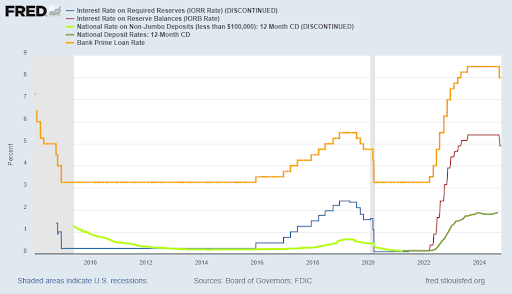

The two graphs below illustrate the speed with which various interest rates adjust. In the first graph, the orange line shows the bank prime rate charged on loans. The blue line shows the rate paid on required bank reserves. This was discontinued when the reserve requirement was eliminated in 2020. However, the line continues in red as interest paid on reserves. And finally, the green lines show interest on National non-jumbo 12-month CD’s until this data was discontinued in 2021 and continues as National Deposit Rates: 12-month CD’s.

The interesting take, as shown in the graph above, is how the prime lending rate moves in lockstep with the rate paid on bank reserves, while the amount paid on the 12-month CD rises much slower from the zero-bound. This occurred both in the 2016-2019 period as well as the post-2022 period.

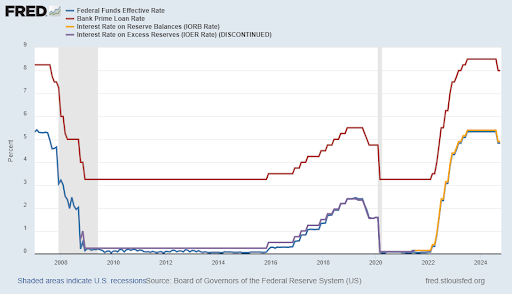

In the graph below the Federal Funds Rate is included in blue to show how it mirrors the interest rate paid on reserves. This is compared to the prime lending rate in red.

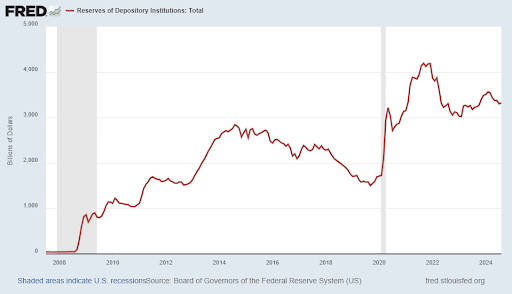

The tremendous buildup in reserves, growing from around 43 billion in 2008 to over $4 trillion by 2022, can be seen in the graph below. In the past, before the Fed paid interest on reserves, the net interest earned by the Fed on Treasury securities they owned would be forwarded as income to the Treasury.

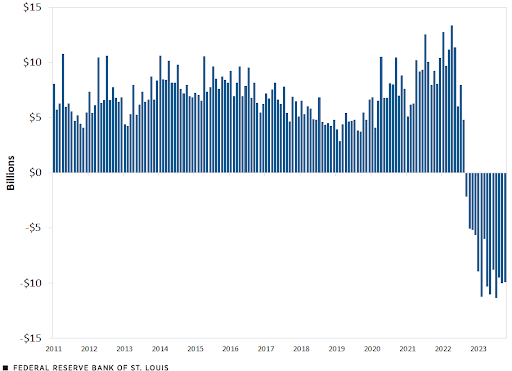

As explained in an article from the St. Louis Federal Reserve entitled, “The Fed’s Remittances to the Treasury: Explaining the ‘Deferred Asset’,” “For most of the past decade [as shown in the graph below], the Fed remitted between $5 billion and $10 billion per month to the Treasury. In fact, between 2011 and 2021, the Fed’s remittances totaled over $920 billion. However, beginning in September 2022, remittances due became negative. Since then, the Fed has experienced a shortfall in earnings that is generally between about $5 billion and $11 billion per month.” The new deficit is being accounted for on the Fed’s balance sheet as a “deferred asset.” The plan is to offset the asset when the Fed returns to positive earnings. Once depleted, they will then resume paying net earnings to the Treasury. Of course, that assumes the Fed will at some point return to a position of net earnings. The Fed is projecting a return to net earnings in 2025 and an elimination of the deferred asset by 2027.

The elimination of the Fed’s earnings results from higher interest rates combined with the obligation to pay interest on reserves, still at nosebleed levels.

Large banks’ ability to earn higher interest rates on their reserves, while growing deposits from those who see them as “too big to fail,” has put them in a position to move slower in rewarding depositors. The Financial Times article calls this a “windfall” of over $1 trillion. Many medium to smaller banks did not have this luxury. They increased their interest paid to depositors so they would not flee to larger banks.

The Fed’s experimental monetary policy, including growing reserves exponentially, removing reserve requirements, and paying interest on reserves, has put them in a predicament for which they don’t know how to escape. Only time will tell how the unwinding will impact the overall economy and financial position of banks and depositors. One unexpected result has already reared its head, a net loss on the Fed’s books resulting in a “deferred asset.” This is really a misnomer because there is no guarantee that this “asset” will ever re-appear.

It seems that Fed policies are designed to help large banks. Am I wrong?

The S&P 500 Index closed at 5,815, up 1.1% for the week. The yield on the 10-year Treasury Note rose to 4.09%. Oil prices rose to $76 per barrel, and the national average price of gasoline according to AAA increased to $3.20 per gallon.

© 2024. This material was prepared by Bob Cremerius, CPA/PFS, of Prudent Financial, and does not necessarily represent the views of other presenting parties, nor their affiliates. This information should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. An index is unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index. Actual results, performance or achievements may differ materially from those expressed or implied. All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however we make no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

Securities offered through Registered Representatives of Cambridge Investment Research, Inc., a broker/dealer, member FINRA/SIPC. Advisory services offered through Cambridge Investment Research Advisors, Inc., a Registered Investment Advisor. Prudent Financial and Cambridge are not affiliated.

The information in this email is confidential and is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended addressee and have received this message in error, please reply to the sender to inform them of this fact.

We cannot accept trade orders through email. Important letters, email or fax messages should be confirmed by calling (901) 820-4406. This email service may not be monitored every day, or after normal business hours.