Executive Summary

Economist John Mauldin wrote several articles reviewing hedge fund manager Ray Dalio’s book “How Countries Go Broke: The Big Cycle.” From Mauldin’s Part 1 article he said: “I described the five stages of Dalio’s Big Debt Cycle. I dubbed them the ‘Stages of Grief.’ Briefly, the cycle goes from a state with ‘sound money’ to a ‘debt bubble,’ then the ‘bubble’ pops, followed by a giant ‘deleveraging,’ and finally reaches a ‘new equilibrium’ from which the next cycle begins.” In Part 2 he describes these stages referencing US history. Please proceed to The Details for further explanation.

For further analysis, continue to read The Details below for more information.

“Debt is the slavery of the free.”

–Publilius Syrus

The Details

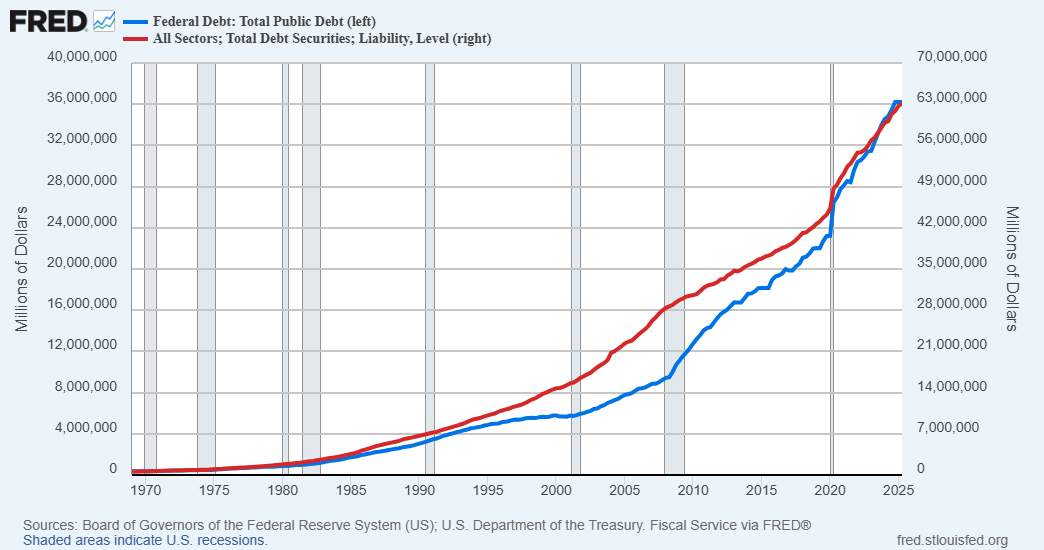

I recently purchased hedge fund manager Ray Dalio’s new book entitled “How Countries Go Broke: The Big Cycle.” While I have not completed the book, I ran across economist John Mauldin’s blog series reviewing (and praising) it. The purpose of the book is to explain how debt cycles work and what to expect from the current cycle. In this missive I provide an excerpt from John Mauldin’s Big Debt Cycles: Part 2 article. Frequent readers of my newsletters might find much of this familiar. I have been writing about the current debt cycle and the government “solutions” which have only contributed to the problem. All of this is based upon the unsustainable use of debt to solve every problem. And how there has been an enormous transfer of private debt to the public sector over the past 15 years.

Previously in Part 1, “I [John Mauldin] described the five stages of Dalio’s Big Debt Cycle. I dubbed them the ‘Stages of Grief.’ Briefly, the cycle goes from a state with ‘sound money’ to a ‘debt bubble,’ then the ‘bubble’ pops, followed by a giant ‘deleveraging,’ and finally reaches a ‘new equilibrium’ from which the next cycle begins.

As this process unfolds, central banks keep adapting their monetary policies as they try to keep the good times rolling. They can do this for a surprisingly long time, too, which may actually aggravate the situation by letting excesses grow larger (cf. Minsky). But in any case, the path is well-trod. The details vary but the stages are remarkably consistent.

I’ll describe these phases using recent US history as an analog [Part 2]. Keep in mind, though, that Dalio shows how the process has been similar in other times and places.

Phase 1: A Linked (i.e., Hard) Monetary System

Dalio says this kind of monetary system prevailed from 1945 to 1971. You may recognize that period as the old ‘Bretton Woods’ era. Other currencies were pegged to the US dollar, which was convertible to gold at a fixed price. It had a good run until Nixon decided to ‘close the gold window.’

Despite its link to gold, Bretton Woods didn’t prevent inflation or recessions. But gold convertibility did put an external constraint on politicians and central banks—which is why it had to go. Credit multiplied faster than the supply of money a limited amount of fixed-price gold would allow.

Phase 2: A Fiat Money, Interest-Rate-Driven Monetary Policy

The US stayed in Phase 2 from 1971 until 2008. The Federal Reserve controlled credit and the money supply by managing interest rates, bank reserves, and bank capital requirements. Nothing was fixed; the Fed could essentially do whatever it wanted. That word fiat (Latin: ‘Let it be done’) was accurate. Our money was worth what the Fed said it was worth. And if the Fed decided to change, everyone had to live with it.

This system ultimately changed in the Great Financial Crisis, when the Fed found that dropping rates all the way to 0% still wasn’t spurring enough credit creation. This led to…

Phase 3: A Fiat Monetary System with Debt Monetization

With interest rates no longer sufficient, the Fed turned to outright buying bonds via various ‘quantitative easing’ programs. I remember that era well. At the time, we all viewed QE as a temporary crisis measure that would end quickly. Ha!

Here’s how Dalio describes Phase 3:

‘This type of monetary policy is implemented by the central bank using its ability to create money and credit to buy investment assets. It is the go-to alternative when interest rates can no longer be lowered and when private market demand for debt assets (mostly bonds and mortgages, though it can also include other financial assets like equities) is not large enough to buy the supply at an acceptable interest rate.’

‘It is good for financial asset prices, so it tends to disproportionately benefit those who have financial assets. It doesn’t effectively deliver money into the hands of those who are most stressed financially, and it isn’t very targeted.’

As Ray notes, not every country limited its GFC-era programs to bond purchases. Some central banks (Japan and Switzerland, for example) bought equities, too. Did it work? Maybe, in the narrow sense that things could have been worse. But we may never know what would have happened because the COVID meteor blew the world into the next phase.

Phase 4: A Fiat Monetary System with a Coordinated Big Fiscal Deficit and Big Debt Monetization Policy

The defining characteristic of this stage is coordination—specifically between fiscal authorities and central banks. We learned in the spring of 2020 that Wall Street has no monopoly on clever financial engineering. The Federal Reserve and the US Treasury Department each used their own power to fill gaps in what the other could do. Congress also jumped in with things like the CARES Act, the Paycheck Protection Program, enhanced unemployment benefits, and more. A giant river of money surged through the economy.

Again, this ‘worked’ to prevent what would probably have been enormous suffering in those months. But it also transferred what would otherwise have been household and corporate debt (much of it unpayable) onto the federal government’s balance sheet, where it still sits today. In fact, we added yet more with additional legislation in 2021–2022.

Phase 4 is still underway in the US. Under Dalio’s framework it will end when debt creation reaches its limit and the ‘bond vigilantes stop buying.”

Phase 5 is the Big Deleveraging. I will hold off on that section for future newsletters. However, it is in this phase where the crisis arrives, and we learn how the powers-that-be choose to deal with it. Whether restructuring, defaulting or some combination of the two, a major reset is coming. We have no way of knowing, other than by examining history, how our leaders will choose to tackle the crisis. In any event, many experts, including John Mauldin, believe Phase 5 is getting close.

The S&P 500 Index closed at 6,664, up 1.7% for the week. The yield on the 10-year Treasury

Note fell to 4.01%. Oil prices decreased to $58 per barrel, and the national average price of gasoline according to AAA dropped to $3.04 per gallon.

© 2024. This material was prepared by Bob Cremerius, CPA/PFS, of Prudent Financial, and does not necessarily represent the views of other presenting parties, nor their affiliates. This information should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. An index is unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index. Actual results, performance or achievements may differ materially from those expressed or implied. All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however we make no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

Securities offered through Registered Representatives of Cambridge Investment Research, Inc., a broker/dealer, member FINRA/SIPC. Advisory services offered through Cambridge Investment Research Advisors, Inc., a Registered Investment Advisor. Prudent Financial and Cambridge are not affiliated.

The information in this email is confidential and is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended addressee and have received this message in error, please reply to the sender to inform them of this fact.

We cannot accept trade orders through email. Important letters, email or fax messages should be confirmed by calling (901) 820-4406. This email service may not be monitored every day, or after normal business hours.