Executive Summary

To understand the risk of inflation or stagflation, it is important to know how “money” is created and what is required of this new money in order to generate inflation. In this missive I review these concepts and show graphs of the money supply, Federal Reserve assets, Federal deficits and the velocity of money. Currently, the concept of inflation is being bandied about by many commentators who often do not seem to fully grasp all of the moving parts. I encourage you to read The Details below to better understand what could potentially have a significant impact on our lives in the decades to come.

Please proceed to The Details for a more in-depth analysis.

“If you dig a hole and it’s in the wrong place, digging it deeper isn’t going to help.”

–Seymour Chwast

The Details

I have previously written why I believe the current spurt of inflation is likely transitory. This conclusion is based upon the amount of debt in the system which will eventually tamper demand while at the same time global supply chains return to more normal conditions. Weak demand and ample, or possibly excess, supply will lead to low inflation or disinflation. However, what could cause inflation to spike over the longer run?

The Federal government has no other option except to attempt to create massive inflation. Only through tremendous inflation will the enormous debt balance and planned future additions be brought under control. But will it be brought under control as hoped? Significant inflation will allow the debt to be serviced with inflated dollars. If long-term high inflation arrives, will it be the result of a booming economy with excess demand, or will it be the consequence of a debt-laden, slow growth economy requiring debt monetization to survive? I believe the result will be the latter which is more akin to incredible stagflation.

It is important to understand how money is created in our economy. There are two main ways that money is created. The first is through bank loans. In the fractional reserve banking system, banks are required to hold a small portion of one’s deposits in reserve and are able to invest or loan the remainder. When someone takes out a loan, the loaned funds create a deposit or “new money” for the borrower. The second way is a little more complicated. When the Federal government runs a deficit, they need to borrow funds by selling Treasury securities to fund the deficit. Normally, the transaction does not create money as money is pulled out of the economy to purchase the Treasuries. However, when the Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) purchases these Treasury securities by crediting the selling bank’s reserve account (with newly created reserves), the monetary base is increased. This increase in the monetary base does not in and of itself increase the M2 money supply (cash, checking, savings and time deposits). In this process, M2 money can be created in two ways. First, the Federal government’s deficit spending of funds derived from the sale Treasury securities to the Fed is called debt monetization. This spending creates “new money” and when deposited by recipients increases the M2 money supply. The second way is for the excess reserves to be loaned out.

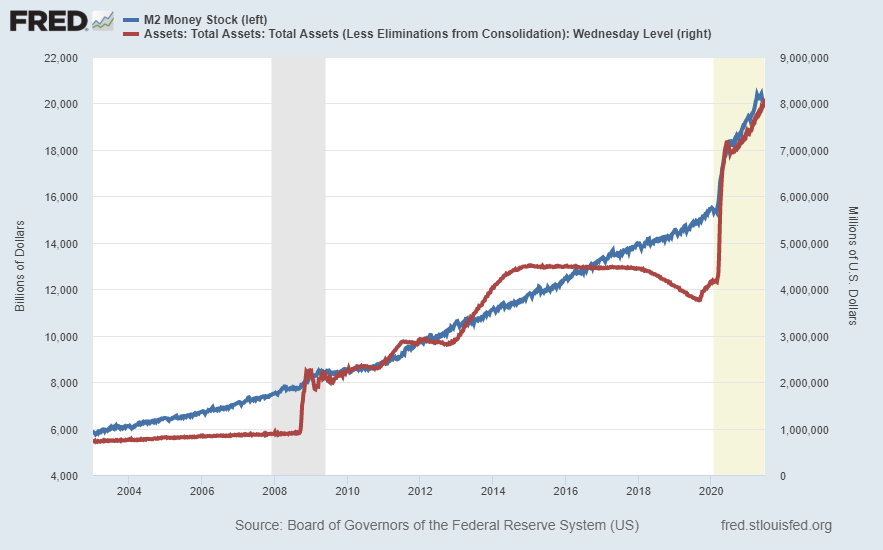

The following chart shows the growth in the M2 money supply (left side) compared to the growth in Fed assets (right side).

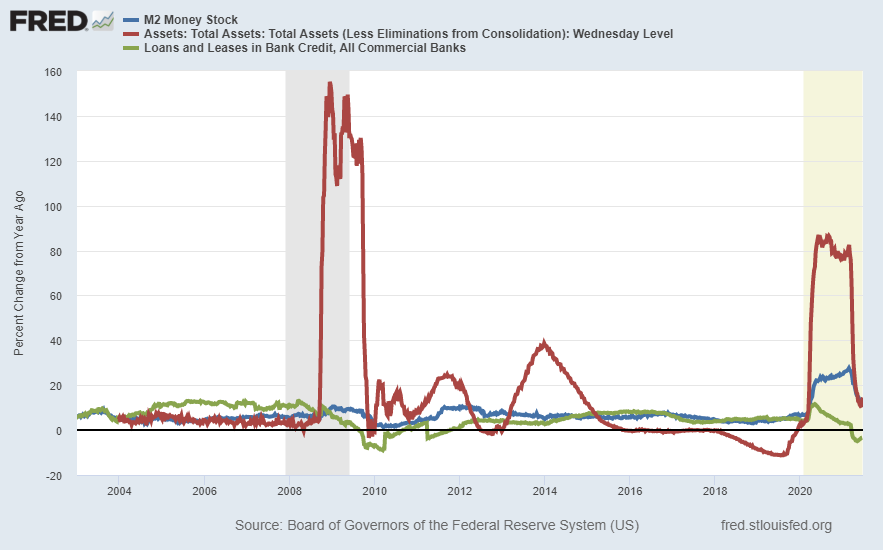

Fed assets prior to the Great Recession were under $1 trillion. Fed asset purchases soared as a result of the Financial Crisis. Then, asset purchases skyrocketed in 2020 due to the Fed’s reaction to the pandemic and new recession. The graph below shows the annual rate of change in the M2 money supply (blue line), Fed assets (red line), and new bank loans (green line). Notice despite the higher rate of change in Fed assets during the 2008-2009 period, because deficit spending was lower than recent deficits, the percentage of M2 money supply growth was lower in 2008-2009 than currently. Loan growth fell during both recessionary periods.

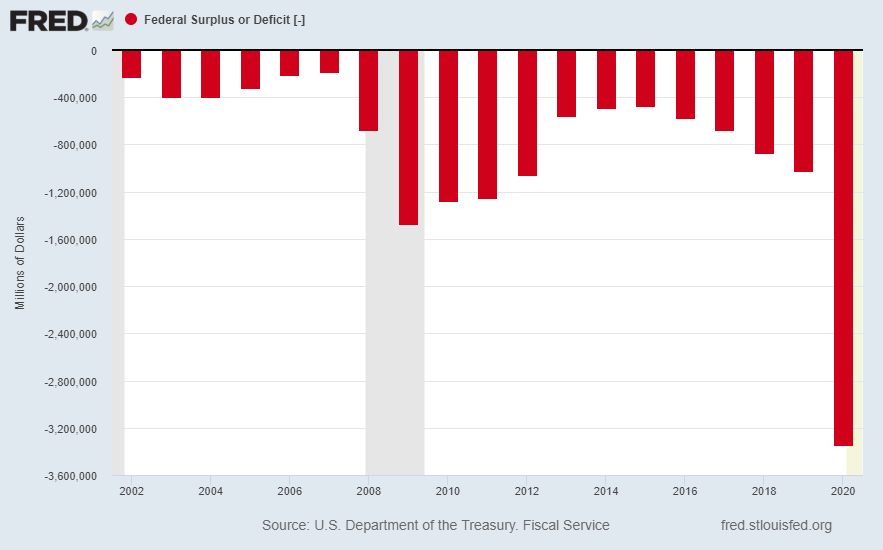

The chart below displays the tremendous Federal deficits over the past 18 years. Notice the extreme deficit for 2020.

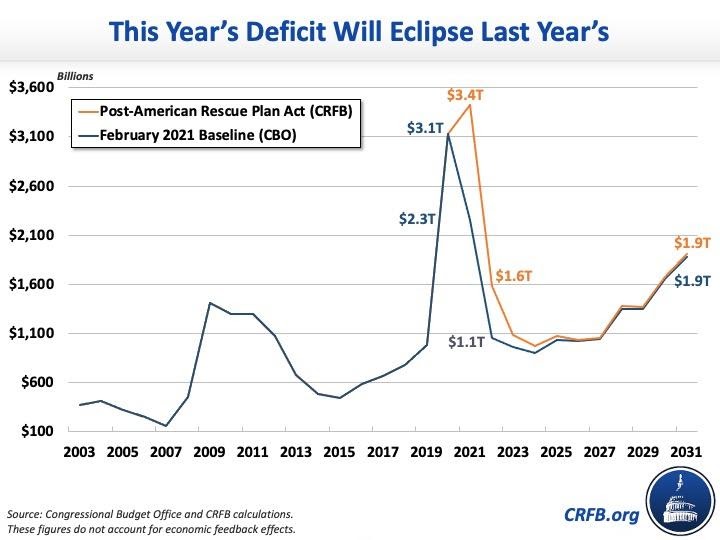

The following chart shows projected future deficits. These projections exclude the possibility of another financial crisis or recession. Even excluding these possibilities, it appears trillion-dollar plus deficits are here for at least a decade if not longer.

As explained in prior missives, the massive debt balances today will act as a drag on future long-term economic growth. Therefore, it is easy to see why I believe the Fed will not stop their QE programs. Debt monetization is here for the long haul.

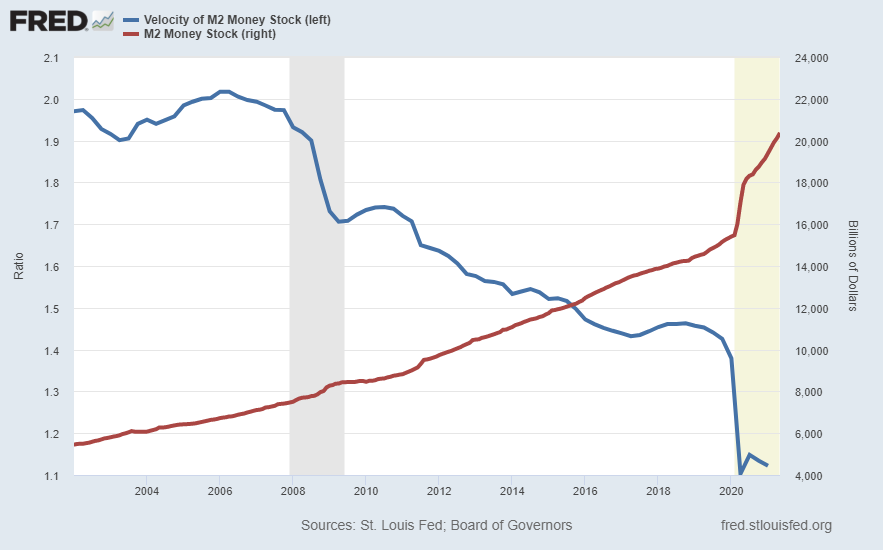

The concern and risk, of course, is that the creation of large sums of “new money” through debt monetization will drive inflation significantly higher and for a longer period of time. But here’s the thing, in order to get inflation, the velocity of money (how often money changes hands during a year) would need to increase. In other words, the bulk of this new money would need to be spent on goods and services instead of saved or used for debt repayment. Presently, as shown below, the velocity of M2 is near record lows even as M2 soars.

The reason velocity has not taken off with skyrocketing M2 is a large portion of the deficit spending was devoted to stimulus payments due to the pandemic. According to economist Dr. Gary Shilling:

“…U.S. households are spending a small and declining share of their stimulus money, using the bulk to build up savings and repay debts, according to a Federal Reserve survey. They spent 29% of the $1,200 per adult they received in April 2020 from the first round of the CARES Act, 26% of the $600 per adult in the second round and 25% of the $1,400 per adult under the most-recent American Rescue Plan. The total transferred from the Federal government in those three rounds was $867 billion.”

The fear is the Federal government will continue colossal deficit spending requiring the Fed to monetize even larger sums. This could include infrastructure spending and additional stimulus benefits – whether for further unemployment benefits or universal basic income (UBI) payments for certain segments of the population. If so, and if these funds are spent on goods and services, velocity could rise. If velocity increases due to government deficit spending during a period of weak economic growth, the stage could be set for stagflation – stagnant growth and high inflation. M2 will continue to grow as tremendous debt monetization continues even as loan growth slows.

The unknowns include at what level and type of Federal deficit spending, monetized by the Fed, will lead to an increase in the velocity of money. The larger future deficits become, the greater the risk stagflation will follow as velocity increases. As mentioned at the beginning, the Federal government has no other option for attempting to control the debt other than through massive inflation. Unfortunately, the enormous debt will cause inflation to come as stagflation – weak growth and inflation.

The S&P 500 Index closed at 4,281 up 2.74% for the week. The yield on the 10-year Treasury Note rose to 1.54%. Oil prices increased to $74 per barrel, and the national average price of gasoline according to AAA rose to $3.10 per gallon.

© 2021. This material was prepared by Bob Cremerius, CPA/PFS, of Prudent Financial, and does not necessarily represent the views of other presenting parties, nor their affiliates. This information should not be construed as investment, tax or legal advice. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. An index is unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index. Actual results, performance or achievements may differ materially from those expressed or implied. All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however we make no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

Securities offered through First Heartland Capital, Inc., Member FINRA & SIPC. | Advisory Services offered through First Heartland Consultants, Inc. Prudent Financial is not affiliated with First Heartland Capital, Inc.